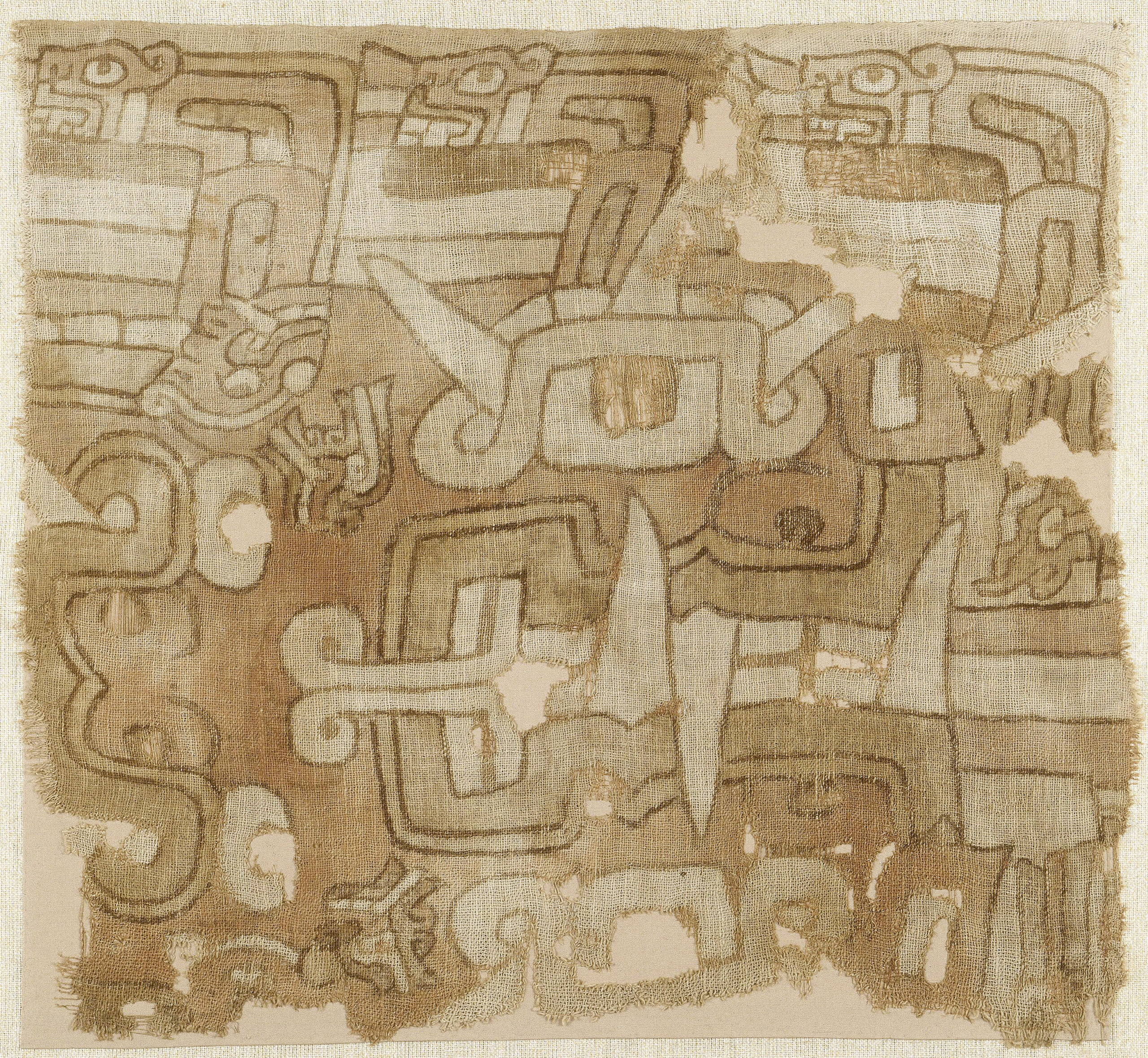

The shaman’s transformation

Numerous visual expressions account for the pre-Columbian shamanic tradition and its specialists. Among the most notable is the one that shows the transformation that occurs to the shaman when in a trance he acquires for himself attributes of different beings of Nature and that of his extraordinary allies. This can be seen in the representations of human figures with animal and vegetable features, such as birds, felines, reptiles, plants and fungi. His allies, for their part, manifest themselves as other human or non-human beings that stand above the shaman’s physical body, called doubles or alter-ego.