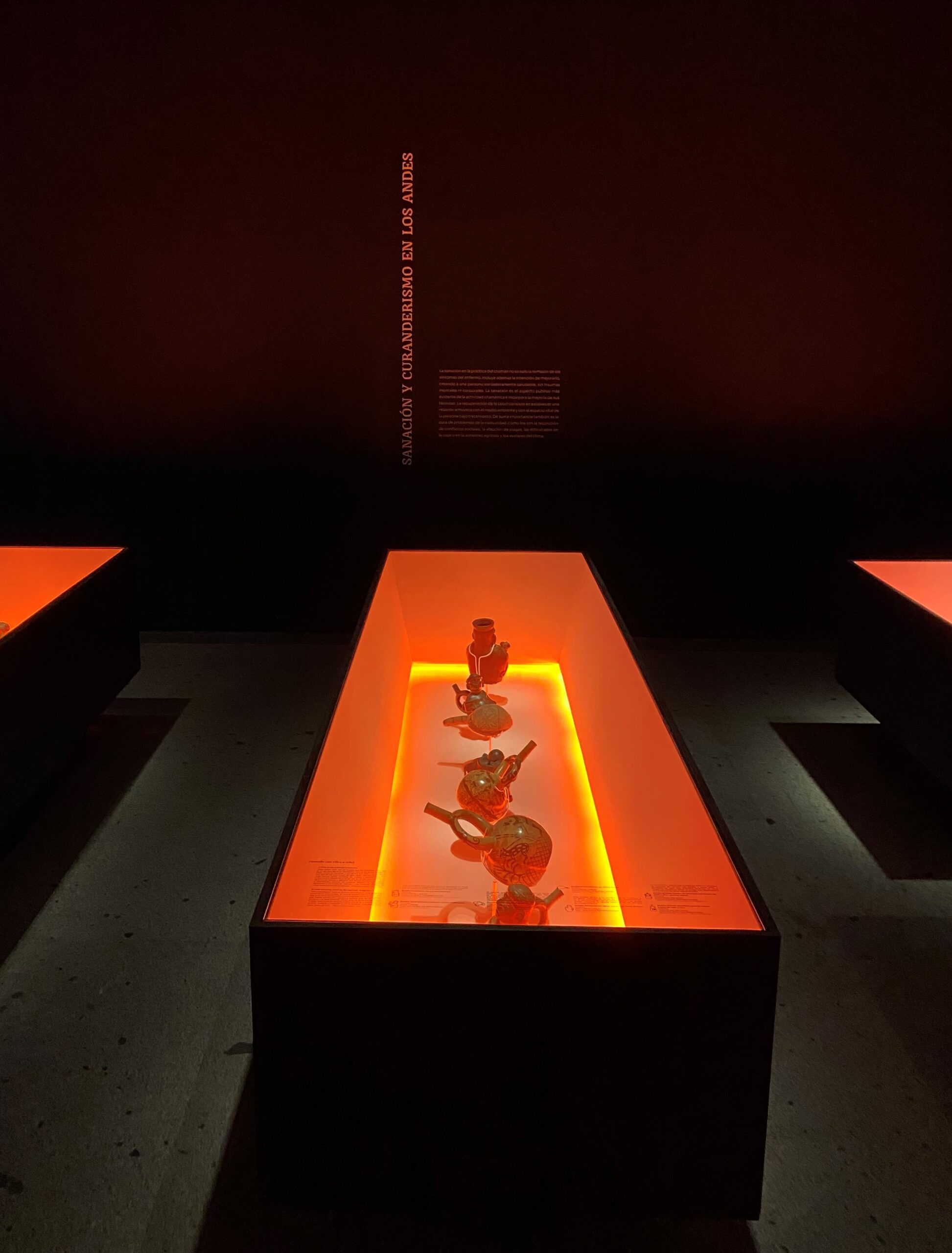

Healing and curaderism in the Andes

The concept of healing in shamanism is not only the remission of the symptoms of the sick individual, but it also includes the intention of improving the patient, creating a truly healthy person without mental or physical trauma. Healing is the most obvious public aspect of shamanic activities, the one that incorporates most of its techniques. The recovery of health consists of establishing a harmonious relationship with the environment and with the living space of the person under treatment. Of utmost importance is also the cure of community problems, such as the resolution of social conflicts, plagues, difficulties in hunting or agricultural activity and the ups and downs of the weather.