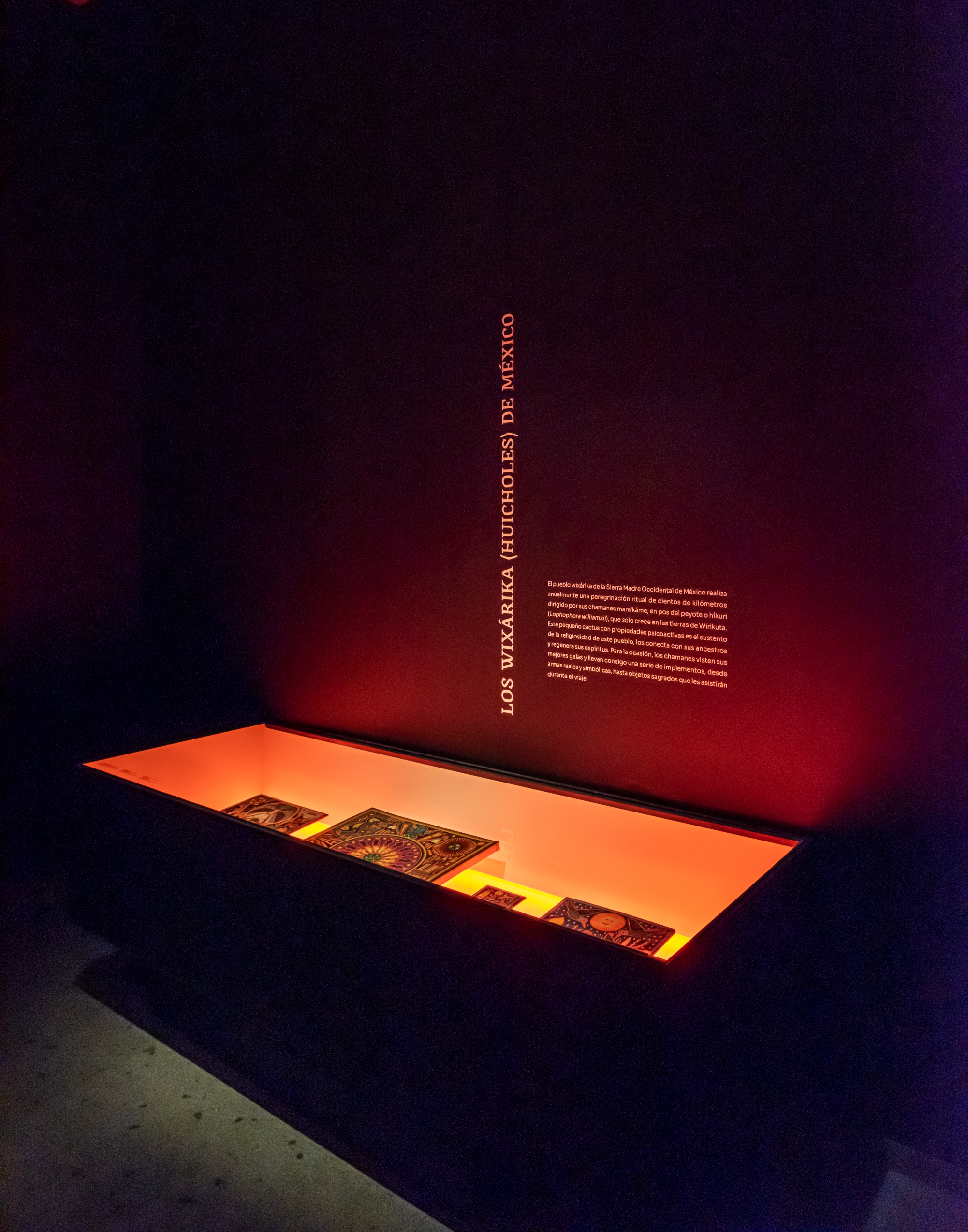

The Wixárika of Mexico

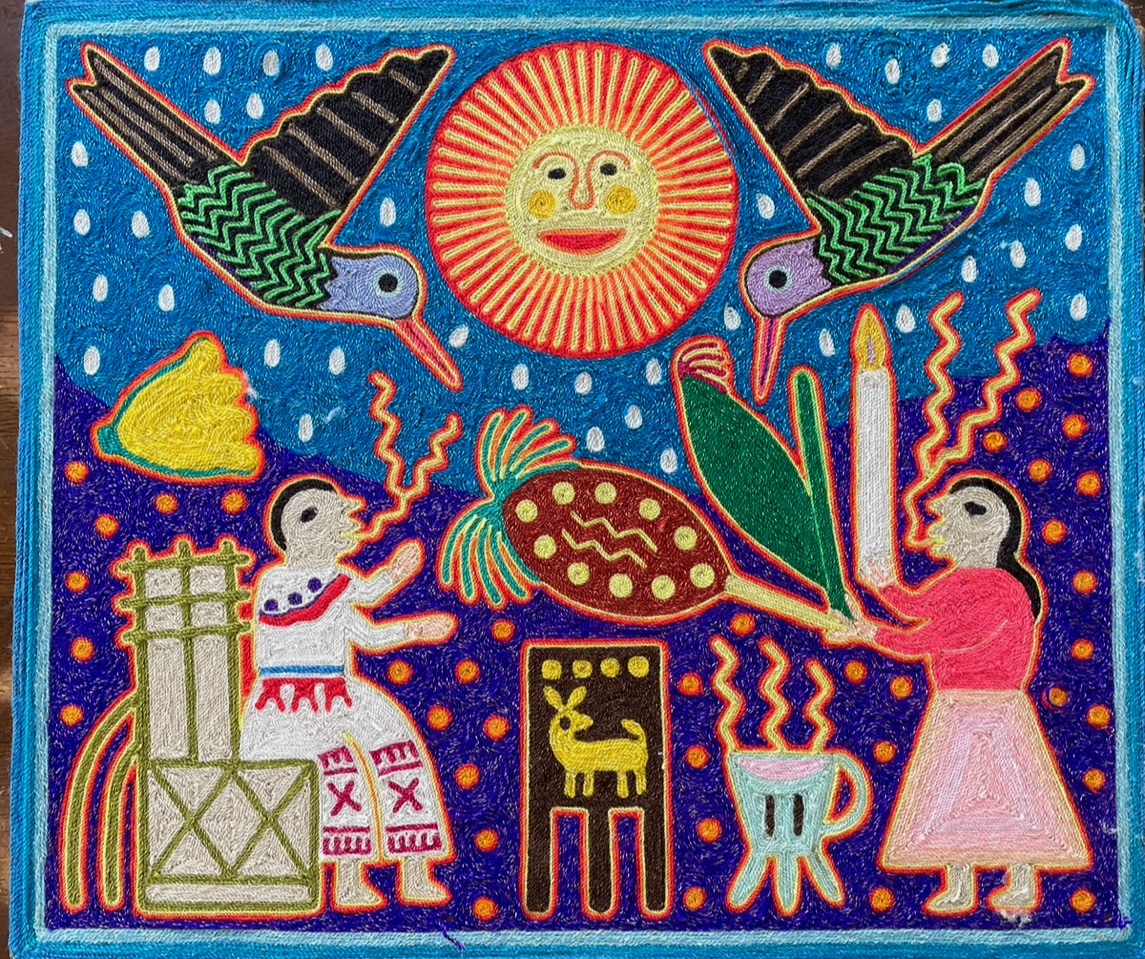

The Wixárika people of the Sierra Madre Occidental of Mexico annually carry out a ritual pilgrimage of hundreds of kilometers under the direction of their mara’káme (shamans), in pursuit of peyote or híkuri (Lophophora williamsii), which only grows in the Wirikuta lands. This small cactus with psychoactive properties is the sustenance of the religiosity of this people, it connects them with their ancestors and regenerates their spirits. For the occasion, the shamans dress in their best clothes and carry a series of implements, from real and symbolic weapons, to backpacks with sacred objects that will assist them during the trip.